Environmental Advocacy and Media in 1970s Alberta

- whytemuseum

- Sep 9, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Sep 17, 2025

By Chris Chang-Yen Phillips, Lillian Agnes Jones Scholarship Recipient 2024/25

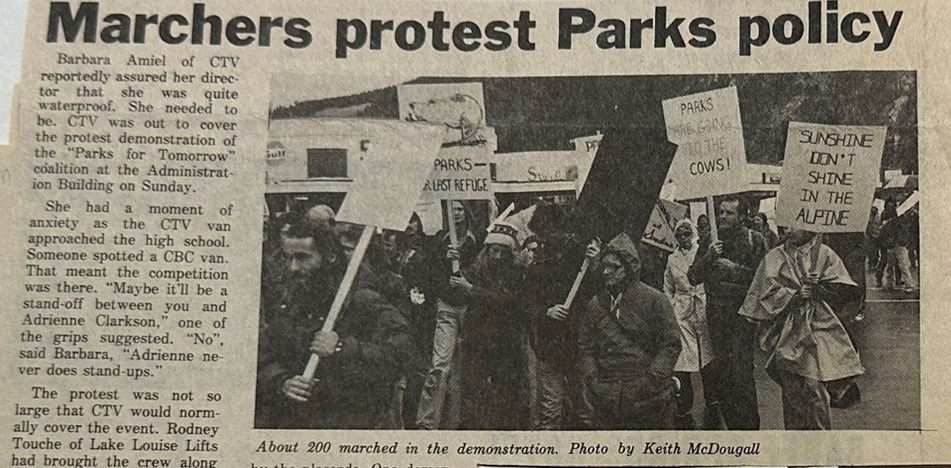

The most unusual thing about the Parks for Tomorrow march through Banff in October 1977 wasn’t the 200-250 protesters putting up with the rain. It was the fact that both CTV and CBC sent news vans out from Calgary to film them. A grip apparently told CTV reporter Barbara Amiel, “Maybe it’ll be a stand-off between you and Adrienne Clarkson.”[1]

Parks for Tomorrow was a coalition of scientists and environmental groups that came together to protect national parks from commercial exploitation.[2] Most urgently, they wanted to stop the Sunshine Village ski resort expansion in Banff National Park, and cattle grazing and haycutting in Waterton and Prince Albert. Their campaign centred around a march down the streets of Banff on October 23, 1977.

Over the past year, I’ve studied their work as part of a research project with the Whyte Museum, supported by the Lillian Agnes Jones Scholarship. The project explores how small environmental groups in Alberta interacted with media in the 1970s. It was a uniquely hopeful time for environmental activists, and many saw media coverage as a crucial part of their consciousness-raising.[3]

Conservation groups across Canada endorsed the Parks for Tomorrow campaign, claiming to represent over 750,000 members.[4] Ground-level organizing was done by a handful of volunteers, many from Banff’s Bow Valley Naturalists (BVN). This article is based on newspaper articles and BVN records at the Whyte Museum.

BVN had about 90 members: locals interested in natural history and protecting Rocky Mountain natural areas. In 1969, they hosted a talk by Stephen Herrero, a University of Calgary professor in environmental studies, who said there was a dire need to protect and create national parks. He encouraged attendees to write to government officials, since “public opinion was a major influence on government decisions.”[5] This advice seemed to resonate. Over the next few years, BVN wrote letters to park officials, submitted “State of the Park” reports, and made statements in newspapers and public hearings.[6]

These strategies helped defeat a $30 million proposal to expand tourism facilities at Lower Lake Louise. The Village Lake Louise plan would have included a year-round visitor service centre, shops, and accommodations for nearly 6000 visitors and staff.[7] BVN joined scientists and other conservation organizations in speaking against it.[8] Jean Chrétien was the federal minister responsible for parks, and in July 1972 he rejected the proposal, concluding it would lead to an unacceptable level of environmental impairment.[9]

In 1977, many of the same activists came together to fight commercial exploitation and political manipulation of parks. BVN President Geoff Holroyd helped rally them to form the Parks for Tomorrow coalition. The Sunshine Village expansion and the decision to allow cattle grazing and haycutting in Waterton and Prince Albert “sparked the coalition’s desire to go beyond the normal avenues of letter writing and dialogue,” says BVN historian Margery McDougall, “which had until then produced only frustration.”[10] They hoped a high-profile protest would make sure their message was heard. Herrero wrote to every conservation group in the Canadian Nature Federation’s national index to ask for support, and many agreed.[11]

Before this, BVN seemed to target media outreach on small local newspapers, which would print their opinion pieces or positive stories about their nature surveys.[12] Parks for Tomorrow organizers decided to invite mainstream radio and TV networks to cover their march, but struggled to figure out what they would need or when.[13]

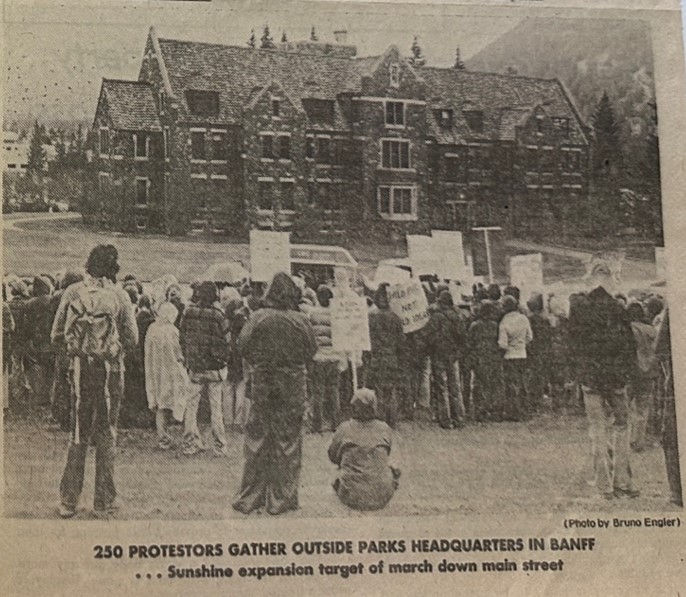

In the end, CBC and CTV sent TV news crews to the protest, and radio stories aired on CBC, CFCN, and CKXL.[14] The Crag and Canyon gave it front-page coverage, with a photo of demonstrators close-up enough to see their ponchos and read their signs.[15] A Herald article included a large photo of protesters in front of the park headquarters. “The marchers slogged through rain,” the reporter said, “to present parks superintendent Paul Lange with briefs and a petition signed by more than 20 naturalist groups representing about 750,000 people across Canada.”[16] For environmental activists, it’s a good day when a major Alberta newspaper portrays you as ordinary people putting up with bad weather to present reasonable concerns.

They attracted positive media coverage by organizing a photogenic event with endorsements from groups representing hundreds of thousands of Canadians. Hosting the march in Banff probably helped, since the park was symbolic of national issues and close enough for Calgary reporters to reach.

In the full article for this project, I explore two more case studies. One looks at Lake Louise journalist Hilary McDowall, who showed frustration with campaigns against ski tourism projects. The other looks at the Whale Society of Edmonton. I hope this research helps environmental groups and journalists better understand each other.

Want to read the full research reports from each recipient? Please visit whyte.org/scholarship

Interested in learning more about Canadian Rockies history? Book a research appointment at the Archives and Special Collections Library at The Whyte. Archives and Special Collections appointments are available Tuesday – Friday, 1:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. To make an appointment or for inquiries email: archives@whyte.org

For more information on visiting The Whyte, visit us online at whyte.org/visit. The museum is open daily from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Endnotes:

1. Before becoming Governor General of Canada, Clarkson was a CBC reporter. Amiel told the grip, “No – Adrienne never does stand-ups.” “Marchers protest Parks policy,” Crag and Canyon, October 26, 1977.

2. Not to be confused with the Parks for Tomorrow conference in 1968, which had no direct relationship besides using the same name.

3. Louise Swift, “From Nuclear Disarmament to Raging Granny: A Recollection of Peace Activism and Environmental Advocacy in the 1960s and 1970s,” in Bucking Conservatism: Alternative Stories of Alberta from the 1960s and 1970s, ed. Leon Crane Bear, Larry Hannant, and Karissa Robyn Patton (AU Press, 2021), 241–52.

4. Margery McDougall, “History of the Bow Valley Naturalists,” May 1980. Document file. 1967-2010. Bow Valley Naturalists fonds. M186. Archives and Library, Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies.

5. “Resume of Meetings and Outings of the Bow Valley Naturalist Club October 1969 to October 1970.” Press releases and newsletters. 1967-1980. Bow Valley Naturalists fonds. M186 / 23. Archives and Library, Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies.

6. McDougall, “History of the Bow Valley Naturalists,” 1980, 4.

7. Chen and Reichwein, “The Village Lake Louise Controversy,” 92; Hilary McDowall, “The Village Lake Louise Plan,” Kicking Horse News, March 1972, 2.

8. “Brief re Village Lake Louise,” (1972?), Bow Valley Naturalist papers. 1970-1990. Jon Whyte fonds. M88 / 816. Archives and Library, Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies.

9. Chen and Reichwein, “The Village Lake Louise Controversy,” 103.

10. McDougall “History of the Bow Valley Naturalists,” 1980, 5.

11. CNF is now known as Nature Canada. Stephen Herrero to all organizations in CNF list of Canadian Conservation Organizations 1975/76, n.d., Parks for tomorrow. 1977-1978. Bow Valley Naturalists fonds. M186 / 24. Archives and Library, Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies.

12. “Vermillion Lakes given careful study,” Crag and Canyon, April 27, 1977.

13. “Notes: Parks for Tomorrow – Organizers meeting,” October 4, 1977. Parks for tomorrow. 1977-1978. Bow Valley Naturalists fonds. M186 / 24. Archives and Library, Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies.

14. “Notes: FON – 20,000,” n.d., Parks for tomorrow. 1977-1978. Bow Valley Naturalists fonds. M186 / 24. Archives and Library, Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies.

15. “Marchers protest Parks policy,” Crag and Canyon, October 26, 1977.

16. “Marchers protest Sunshine expansion,” Calgary Herald, October 24, 1977.

Comments